“Booby traps?”

“Oh, yes. But I found the clues that will safely take us through, in the Chronicles of St. Anselm.”

“But what are they? Can’t you remember?”

“I wrote them down in my Diary so that I wouldn’t have to remember.”

Henry and Indiana Jones in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade”

The goal in science is not to read literature, it’s to do something with this literature, the works of others, to build on it (or re-build while being aware of it). To do so, you need to have the information you read available for your own works.

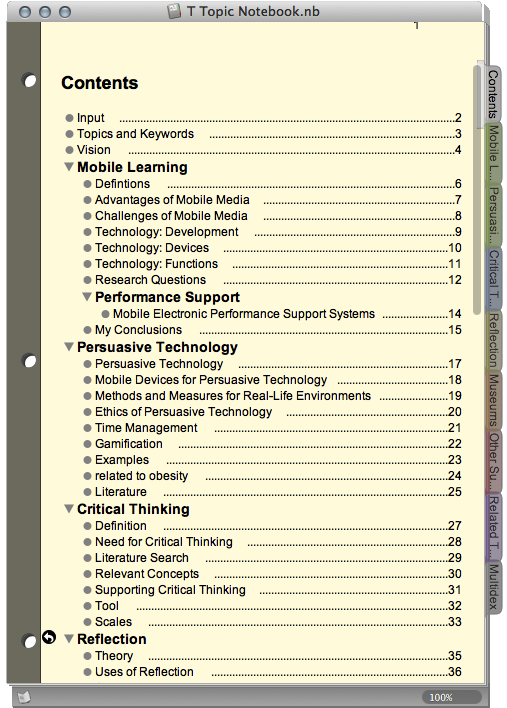

One interesting way to help you remember and work with the information you read (and create) is to use a topic notebook. It contains all the information you have read about a (series) of topics and your own thoughts about it.

To be useful, it must have the following functions:

- clear structure — You have to find quickly what you search for, this includes:

- the overall structure (the “notebook” itself), e.g., the way the topics and subtopics are ordered, and

- the “pages”, e.g., the information about each topic.

- absolutely clear source information — Note that plagiarism kills careers and that there is no excuse for sloppy research.

- quick and easy to find, enter, edit, etc. — You will use it a lot, working with it should be a breeze.

- easy to create derivative works from it — E.g., using it as the basis for a paper or a book (correctly cited!).

Personally, I highly recommend Circus Ponies Notebook for this purpose, as it fulfills these requirements perfectly (for me):

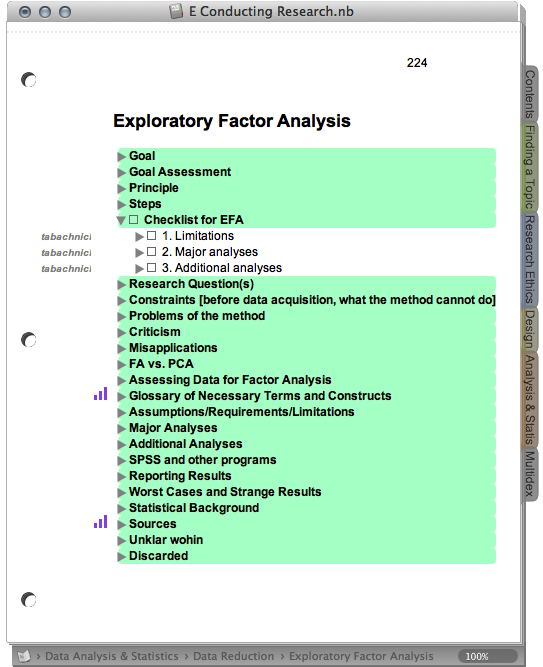

- clear structure — The notebook metaphor makes it easy to work with different topics, while the outliner pages make it very easy to deal with lots of information on little space. You can use multiple notebook or one notebook for different topics, create sections, and the like.

- absolutely clear source information — If you tag each outliner cell with the source information (select all and assign the source information, e.g., miller_1995, as keyword) you have the source information unobtrusively available at all times as it sticks to the information.

- quick and easy to find, enter, edit, etc. — In contrast to a wiki you can quickly type text into the cells, change the outline by drag and drop, etc.

- easy to create derivative works from it — You can copy and paste relevant outline cells to another notebook (careful which kind of copy & paste you use, use the one that preserves the keyword/source tag information), using the information as LEGO® building blocks for your own work (when writing, show the keywords (cmd + k) to know which works you need to cite).

However, this is only one solution and there are probably other programs with which you can do this as well. The concrete program is not that important — the function it fulfills is.

You might want to keep the following things in mind if you decide to keep a topic notebook:

- Take only what you need … — The goal of a topic notebook is not to become a verbatim copy of all the works you have read, but to collect the relevant information. Relevant for your work. So you have to set the focus and you have to select from what you are reading.

- … but preserve the context — When you select information, make sure that you preserve the context of that information. No matter how strongly you break up a text you read, make sure you know later what the information meant — based on what you write down! Don’t assume you remember it five years in the future! The notebook should externalize your memory, so make sure it is correct. For example, if an author lists three major influences and you are only interested in one, copy the information about the one into your topic notebook, but also write down that the author saw this as one of three influences. Otherwise you might later cite this author wrongly (e.g., “x also saw y as influence to …” instead of “x also saw y as one of three influences to …”). You are moving away from the actual source (the paper), you have to, but you also have to preserve the context! Otherwise you misrepresent the author — something that not only hurts your career but also incurs (rightfully) negative reactions by the authors.

Pat Thomson wrote an excellent posting on her blog:

“So the problem was the cherry-picking of something that was useful to the doctoral researcher, without due recognition of my overall argument. Anyone reading the doctoral thesis would conclude that my work supported the case made in the thesis. In reality of course, the doctoral research was diametrically opposed to my own. All it would have taken for me not to feel seriously misrepresented was for a simple caveat to be made in the text, or even a footnote, which said that my definition and empirical work had been used, although my actual argument was very different from what this thesis was suggesting.” (Thomson, 2013)

And she concludes with:

“The lesson here goes to understanding that pieces of any academic work/text fit within an overall argument. It’s important to understand and acknowledge their place in the whole, as well as their utility as a part.

I always suggest in workshops and writing courses that when doing literature work and when noting texts, one of the very first things to do is to summarise the argument. I think after writing this post I might add that it’s important to use this information about the argument later when choosing citations. It’s critical when using parts of texts to use the summary of the argument to avoid the situation where textual bits and pieces are used willy-nilly to misrepresent the writer’s overall intention.” (Thomson, 2013)

Adhere to it. Sloppy research is a waste of time, money, and effort — yours, your colleagues, the general public. And it hurts your career. - Part of the context is knowing the quality of the information you collect — There are huge differences between, e.g., a blogger’s opinion and the results of a meta-analysis. When you collect information make sure you annotate it if it is an assertion (e.g., “mobiles improve learning”). Be clear about it — is it an opinion? A theoretical derivation? A study result? A result from a meta-analysis? You can get this information later when you look at the source information, but it’s easier and actually beneficial to do this early on. A large part of being a scientist is being critical — do you trust this information to build your own works on? Would you use this brick to build a bridge? You are putting the weight of your career on it! Make sure it is strong enough.

- Differentiate between your works and the works of others — If you have each information unit (e.g., an argument from a paper you deem relevant for your work) tagged with the source information, this is fairly easy. But you can also use, e.g., italics (for verbatim quotes) or colors. While you can work with other people’s ideas/findings like you would with LEGO® bricks, make sure to add your own ideas. Write down your thoughts, ideas, questions. And always be clear what was your idea and what you have found in the literature!

- Trim and reorder regularly — Over time the topic notebook will grow, so make sure you are not swamped by the amount of information. Outliners are really helpful here, as you can write more general issues in the top level cells and use the child cells to add the detail information. The nice thing about digital collections is that you can quickly copy & paste/move information.

- Avoid duplicating topics/issues within or between notebooks — Copy & pasting digital information makes it easy to add the same information in different places. Sometimes this makes sense, e.g., an argument that applies to different topics you are interested in. However, be careful not to add the same topic/issue multiple times. For example, if you are interested in “learning in museums” and “learning with mobile media”, decide where you put “mobile media in museums”. Do not add “museums” as subtopic of “mobiles” and “mobile guides” as subtopic of “museums”. This would become problematic the second you add new information — you have to add it to them all, which takes time and is likely to produce errors and a disorganized notebook. Use “see …” and refer to the place where you put in this information. This is the disadvantage of hierarchical structures (and any notebook is hierarchical), but on the other hand, this hierarchical structure makes it possible to deal with large amounts of information. A network structure (e.g., a Wiki), links (supported in CPN), replicants (supported by some outliners) might avoid this problem, but a non-linear structure makes it very hard to be sure that you have fully scanned the information about a topic.

- Use the appropriate level of detail — You can go down into the details with tables of findings and exact values, you can also focus on the overall argument, you can do even both (the nice thing about outliners — you can fold in the information not needed at the moment and keep information aggregated in the higher level cells). But make sure you operate on the right level of detail and/or be able to switch between different levels of detail when needed. Digital makes it easy to copy a lot and get lost in the details quickly. Regular restructuring, trimming and aggregating and summarizing information is needed.

- Do something productive with the topic notebooks — A topic notebook has no real value of its own. It ensures that you have the information you need for your work in one place, it externalizes your knowledge and allows you to deal with complex information and provides you with easy access to it. Use it regularly and do something with it that advances your career. Blog about it, design studies, conduct experiments, write and publish papers! Organizing should assist your creativity, don’t use your creativity to optimize your organization without getting concrete products from it.

The great thing about a topic notebook is that you have the information you have read available — immediately and independent of your available cognitive resources. It’s fairly easy to use the topic notebook and copy and paste the relevant cells (mind the context!!!) to another notebook and create and article or book. However, make sure that you have an overall idea what you want to do with this information, e.g., a question to ask/answer in the scientific discussion, and that you add something meaningful to it. Otherwise it’s only “a transference of bones from one graveyard to another” (to quote J. Frank Dobie regarding the average PhD thesis).

After all, the information you have is useless unless guided by a purpose, and damaging if not used correctly. But organized you can do things of astonishing power and complexity that you never thought you were capable of.

Nice posting. Great advice. I use circus ponies in a similar way. I also supplement my topic writing with an author reference created in VoodooPad. I name each page in the author reference with a distinct title using author-date-page number-and context. When I am ready to write a topic in circus ponies, I use VoodooPad’s search capabilities to give me a complete listing of authors and related text. It’s been a real time saver, and helps me keep my content separate from authors’ material.

Ah, I didn’t know VoodooPad … interesting … have to check that out …

I do use electronic notebooks and have a variety for different topics. However, I find the simple act of actually writing in a paper notebook tends to help me generate my own ideas and create links between different material. I then transfer info out of my paper notebook into electronic ones. So the electronic notebooks are essentially a backup that allows me to group the information in different ways.

Hoi Jeannette,

I had a look at your posting about how you work — I gotta say, your handwritten notebooks look not only useful, but also very aesthetic. While I jot down ideas by hand sometimes to capture them and love to work with Magic Charts to develop ideas over longer periods of time, I couldn’t work with paper notebooks. But mostly because my handwriting is too … erratic (I took a calligraphy course a few years ago — the teacher looked at my carefully copied letters and went: “Normally they should look all the same, but in your case better try to make the lack of consistency a style.”). But it shows again that work methods are very personal.

BTW, if one day you want to keep the notes as remembrance but not the paper, you can use a document scanner. Some time ago I scanned notes I made in my youth (using a document scanner, see also here). Worked really well.

All the best

Daniel