“But for such a work you must have needed books — had you any?”

“I had nearly five thousand volumes in my library at Rome; but after reading them over many times, I found out that with one hundred and fifty well-chosen books a man possesses, if not a complete summary of all human knowledge, at least all that a man need really know. I devoted three years of my life to reading and studying these one hundred and fifty volumes, till I knew them nearly by heart; so that since I have been in prison, a very slight effort of memory has enabled me to recall their contents as readily as though the pages were open before me. I could recite you the whole of Thucydides, Xenophon, Plutarch, Titus Livius, Tacitus, Strada, Jornandes, Dante, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Spinoza, Machiavelli, and Bossuet. I name only the most important.”

“The Count of Monte Cristo” by Alexandre Dumas

Once you are searching for and finding literature related to your topic, you have to deal with this literature. Before you can read and do something with it (i.e., build your own works with the correctly cited ideas of others), you need to manage it, which means:

- have the relevant literature available, i.e., make it possible to quickly sift through the hundreds of papers you have found to find the one’s you need at the moment, and

- ensure that you will always know for certain where the ideas/building blocks you use for your work came from (otherwise you will be accused of plagiarism, even if you did not mean to ‘forget’ the source)

So how do you manage your literature?

There are a lot of arguments for managing the literature digitally — even if you print it out to read it. PDFs are very future proof (you can probably still open them in 50 years) and in case you move or fire/water strikes, you still have your literature collection. There are also ways to quickly highlight relevant parts of texts and export only the highlighted parts with your notes (more on this in one of the next postings). But to work with the literature digitally, you need your literature available as PDF files — in good quality and unprotected (some PDF files are saved in a way to prohibit copy & paste or printing, which makes them practically worthless).

Making your literature available digitally

Following Tips might be helpful to have your literature available digitally in a way you can work with it later:

- Get the Original Journal PDF (ideally with CrossMark): If in any way possible, get the original PDFs from the journal. Not only is this usually the best quality, with features like CrossMark (if supported) you can easily check for updates to the article in the future. Unfortunately, an errata, corrigendum, notice of concern or retraction can happen and you should know when a building block of your work gets called into question — and crumbles away.

- If you scan your literature, scan one page, not double pages: Many universities and copy centers have xerox machines that allow you to scan the book/article as PDF. Often you could scan two pages at once (e.g., from a DIN A5 book, which results in a landscape format A4 scan). However, while this is faster, it also makes it harder to read the source digitally later. If possible, scan single pages.

- Keep the original scans but create a reading version: You can reduce the file size of a PDF (on cost of the quality, but often hard to notice) and use OCR (which also changes the scan somewhat). In many cases, you should do both, BUT make sure that you store the unaltered original scan somewhere safe. First you might want to get back to the full quality, e.g., if you want to use a figure or print it in high quality. Second you might process the PDF in a way that makes it unreadable with some PDF readers. For example, there are some optimizing options in Acrobat that make the file unusable for other PDF readers like GoodReader or even the preview in DEVONthink — they show only blank pages (Acrobat still shows the text). Personally, I only use reduce file size (without the optimization options) and OCR — and I always store the Original Scans in another folder.

- Remove the scan borders: Often scans have black borders around it (the scanning area was larger than the paper that was scanned, and as no light is reflected the scanner takes it as ‘black’ (or captures your hand holding down the book). Software like Acrobat (full version) can crop these pages to automatically remove the black borders. See “Document” – “Crop Pages”. This is especially helpful if you print the pages — it will save ink. It will also allow you to display the text larger on digital devices (e.g., on an iPad). If you want to print it larger, you can allow Acrobat to use the whole page when printing (in the print menu: Page Scaling: Fit to Printable Area) — or you can force it to use the original size (Page Scaling: None).

- If possible, get it without DRM: Digital Rights Management — an euphemism for “you bought it, but you cannot decide what to do with it” — often prevents you from copy & pasting text, printing it, sometimes even from opening it later. While I can understand it with rented movies, it’s a pain in the ass for academic work. However, there are a couple of ways that can help you gain access to the content itself for your purposes:

- If you can print it, print it and rescan it: The quality will suffer and the OCR (optical character recognition, makes the text from the scan readable for the computer and allows you to select-copy-paste the text) might suffer, but it’s better than nothing.

- Look for Plugins: Some programs have plugins that can remove the DRM (apparently there is a plug-in for Calibre which will remove the DRM from Kindle books).

- Try other software: Some Apps ignore DRM, e.g., for PDFs. This might allow you to access (select-copy) the text, which you can then export (paste into an email).

- Look for an unprotected copy: Some authors have preprints available. Check whether the content is the same, then use the pre-print version.

Storing the Literature

Once you have the files on your computer, what do you do with them? You need to collect them, i.e., put them into a structure that allows you to deal with them. (Un)Fortunately, there are countless ways available to store your literature digitally. This gives you a lot of options, but you have to find out what you need from your storage solution and how you want to work. However, a few things are well-worth adhering to in any case:

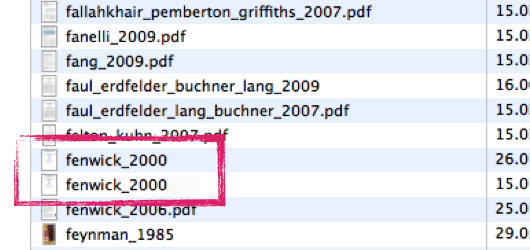

- Standard notation format: No matter which system you use, rename the files into a standard notation format (some reference managers do it automatically, personally, I would do it manually). There are people who use consecutive numbers as file names, but I think this is a very bad idea — the number has no meaning and you need another source (e.g., a list in a text file) to find the literature you look for. What I highly recommend is using the names of the authors and the publication year, e.g., james_1954 for an article by James, published 1954. I would use lowercase and “_” for ” “. If there are multiple authors, simply add them as well (up to 7, if more than 7 only first author and et al.), e.g., james_fowler_1960 for an article by James and Fowler, or james_et_al_1962 for one where James collaborated with more than 6 other authors. This notation helps you to remember the author names and gives you the information immediately how current the source it. It is also the standard citation format in a lot of scientific disciplines (you would use, for example, James, 1954, in a text) and it will prevent downloading (and reading!) duplicate articles (trust me, it happens).

If a combination of authornames and year occurs twice for different articles, add ‘b’, ‘c’ … for example, james_1954, james_1954b, james_1954c, … . Do not change the first source you had from james_1954 to james_1954a, otherwise you run into problems if you already used this notation in your notes. Trust me on this — it will make dealing with your literature and getting to know the field (the other scientists who work on the topic) much, much easier. Do this as early as possible, e.g., when — during your workday — you have to do something where you do not need to think much. -

Using a common schema for the file names of your literature will allow you to quickly find duplicates. It will either produce an error in Finder/Explorer because a file with this name already exists or you can spot it quickly in a program that allows for the same file names (here: screenshot from DEVONthink). - Get the source: Luckily, most journal papers print the necessary citation information on the first page, but not all do. And for some sources, almost no information is available. Whereas Google usually allows you to find a source again (copy and paste some text from the source into the search field), make sure to copy & paste the necessary information into the file immediately if this information is missing. Nothing is worse than having found a great text and you cannot use it for your work because you cannot cite it correctly.

- Get the file: Some sources are websites (e.g., blog articles). No matter what you do, get the sources as a file on your computer. Yes, there are programs that allow you to quickly create an online scrapbook or a collection of interesting links, but the Internet is highly unstable regarding its content and even the Internet Archive does not store everything. You do not want your sources evaporate because the website is no longer available (e.g., someone cleans his/her blog or a company/organization folds). Sometimes this means printing the website as PDF file (Mac can do it natively with File – Print – PDF, there are Printer-Plugins for PCs), sometimes this means making a snapshot (using the “Grab” software on the Mac, or the “Print” key on the keyboard for PC, then a graphic program to get the image from the clipboard to a file). DEVONthink has a nice Browser-Plugin that allows you to capture a website easily (the paginated and the unpaginated option differ, and it does not work with website where you have to log in, so check the results!). Check whether the URL is saved in the file and the date when you had accessed the page. This is often an option when you print a website as PDF and you might need this information later.

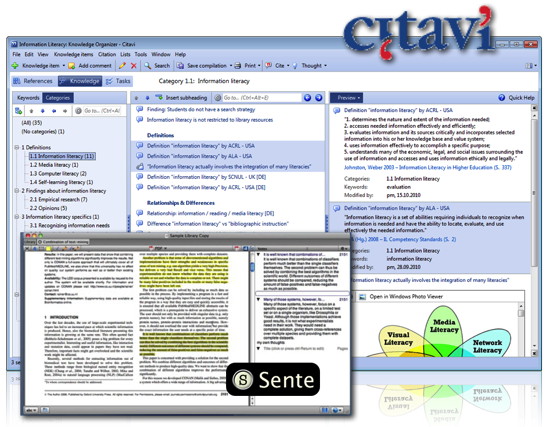

- Careful with reference managers: There are a lot of reference manager available (also called reference management software, citation management software or personal bibliographic management software), e.g., Sente, Papers, Zotero, EndNote, Citavi, etc. (you find a good list of available reference management software on Wikipedia). Reference managers are essentially a database which store the files and have predefined text fields for each content type (e.g., journal, conference proceedings, book chapter). If these fields are filled out, the reference manager can automatically generate the citation in the correct format for your paper (e.g., APA style). Many reference manager are also connected to databases or use a browser plugin to automatically get the citation information, although success varies. However, if filled out correctly, this is very helpful when you write your article. You can use a plugin in your writing software to refer to your reference management software when you cite something and once you are finished the press of a button creates your reference section automatically.

However, I see two main disadvantages with reference managers: First, it (often) forces you to enter/search for the citation information before you use the source. This can slow things down when you search rather broadly and do not yet know whether you will use the source in the first place (researchers sometimes turn into squirrels when it comes to literature). The alternative is either to skip this step — which leaves you with an incomplete database (makes the use difficult and unpleasant) — or to store the “not quite sure yet” sources somewhere else, which quickly turns into an organizational nightmare. Second, reference managers make it hard to actually do something with the literature. Some reference managers only have a simple text field for notes (rarely useful), while others have integrated highlighting and allow you to make detailed notes in the PDF files (e.g., Sente, which can export these highlights/notes) or allow you to build a knowledge database (e.g., Citavi). However, I find these solutions inconvenient and too limiting.

In any case, take care of the stability, speed, ease of use of the software you use — your literature is a major part of your building material for your own work. If there are problems with it, your work and career suffers. Look critically at the features — some (e.g., summaries in Twitter 140 character style) are a waste of time.

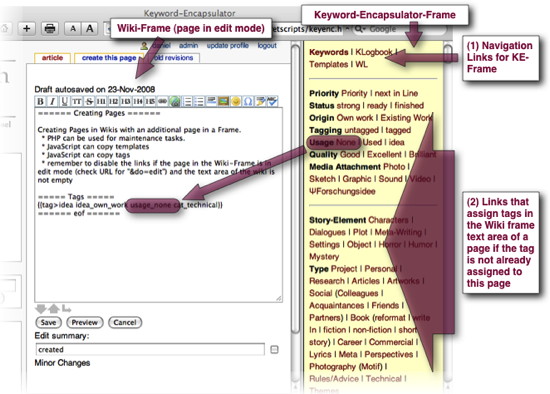

Personally, I will use Mendeley for the literature I have actually read and only to use the social networking functions of Mendeley. I store my literature as PDFs in a DEVONthink database — much more convenient for me. [Update: Until it becomes clear how Elsevier treats Mendeley, I no longer recommend using Mendeley (currently looking for another solution).] - Create an optimized workflow: Managing literature is something you have to do for the rest of your career. Given the amount of time you spend on it, even small savings add up to huge gains over time. For example, if you use a wiki to store your literature (I did this once), use templates to quickly create new entries (see Ferret Frame).

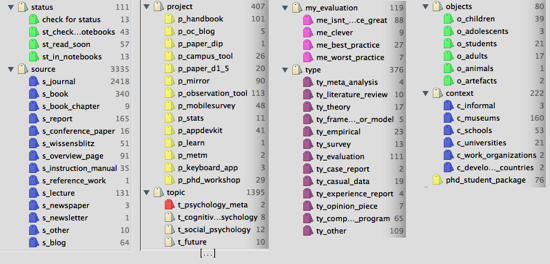

- Use (hierarchical) tags and a taglist: Tags can be very helpful to sift through your literature — if you use them wisely (see the section on tags in Organizing Creativity). Think in advance which tags you need and build them up when you get a feel for the kind of literature you have and the areas where you need to quickly sift through a lot of files. For example, if you have 1000 articles and all are from journals, a tag ‘journal’ makes no sense. If, however, you have a mixture of journals, books, conference proceedings, etc. and you use the format of the source to find them, the tags journal, book, conference_proceeding are helpful.

Often using tags is a question of the right level. For example, if you are interested in “research ethics” consider whether tags a level higher (e.g., “ethics”, “research”) or a level lower (e.g., “privacy”, “data security”) are not better suited.

Many programs automatically display tags. This will make it easier to find the tags and to prevent you from entering synonyms (e.g., conference_proceeding vs. conference_paper) or confuse singular and plural forms.

Ordering tags hierarchically is often a very good idea. For example, using a tag like “source” and then the subtags “journal”, “book”, “conference”, etc. It will make working with tags easier and if you can search for “NOT” you can display all PDFs that are not tagged with the higher order tag (e.g., “source”), allowing you to quickly find the untagged PDFs.

Personally, I use the following tag list:

Some examples to store literature

Like written, there are countless ways to store literature. I highly recommend renaming your literature in the standard notation (authorname_authorname_…_year) and trying out a few solutions. For example:

Sente or Citavi

Both go beyond storing literature in a database. Sente has an interesting note taking feature and there are scripts that allow you to export your notes. Citavi aims to help you in managing knowledge.

Mendeley [Update: Until it becomes clear how Elsevier treats Mendeley, I no longer recommend using Mendeley (currently looking for another solution).]

I think the main advantage of Mendeley is the social network behind it. I just (re)started using it and while I will not use it to store my literature, I am hoping that it will allow me to find other researchers who work on similar topics.

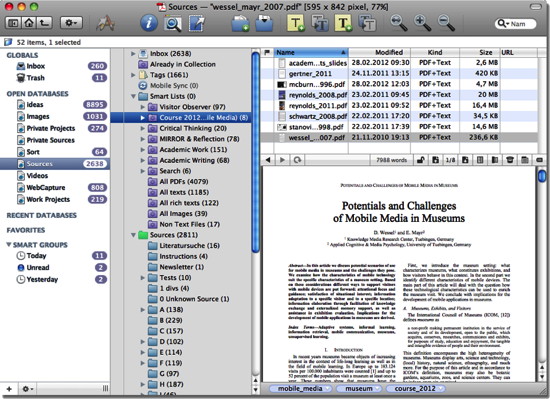

DEVONthink

I use DEVONthink to store my literature. It is a very powerful software that looks like the normal finder in Mac, but gives it much more features. You find more information on DEVONthink in these postings: A very quick introduction to DEVONthink, DEVONthink — Second Impression and some Tips, Literature Management with DEVONthink, or DEVONthink.

I think the main advantages of DEVONthink for literature storage are the speed and ease of use, that it automatically detects duplicate files (looking at the content, not the file name), has a good tagging function (incl. hierarchical tags), supports RSS feeds, and much more.

Note that the issue here is storing the literature — I use other software for reading it and dealing with the notes (more on this in one of the next postings).

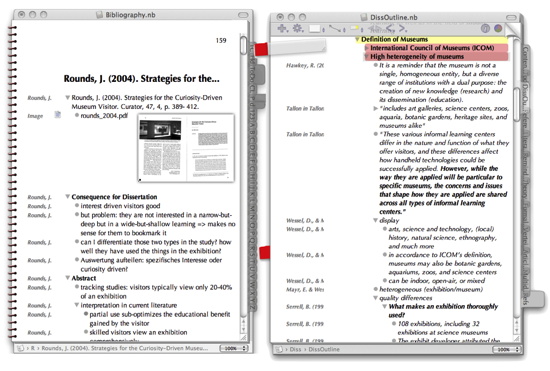

Circus Ponies Notebook

I have written a few postings on using Circus Ponies Notebook for Literature management (e.g., Circus Ponies Notebook for Academic Writing (e.g., Thesis Writing) or more general: Circus Ponies Notebook: The Best Tool for Structuring Creative Writing Projects (esp. Research Projects)). I do not use it anymore to store literature, but to handle the notes that I take when I read literature. The outliner function which allows tagging each outliner cell with the source information is invaluable! More on this in one of the next postings. But you can also use Circus Ponies Notebook to actually store the files.

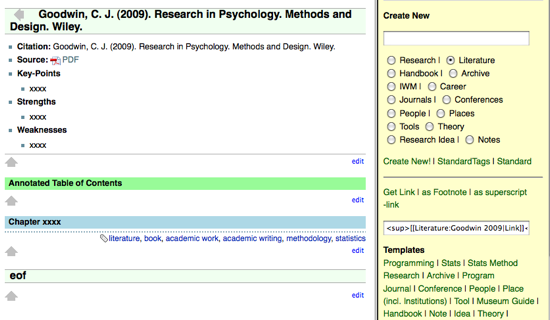

Wiki (e.g., DokuWiki)

When I started organizing my literature, I began using a Wiki (DokuWiki, for an overview of different Wiki software see Wikipedia). You can make your work easier when you use frames and JavaScript to allow for templates and easy tagging. See Ferret (Frame and JavaScript Enhanced Wiki) for more information.

I do not use a wiki anymore for various reasons, mainly, that it put too much focus on layout, the notes are not easy to use, I do not need the collaborative aspect that is inherent in Wikis. But it was a good starting point and it might be something for more collaborative use of literature.

Literature Recommmendations

- Wessel, D. (2012). Organizing Creativity. How to generate, capture, and collect ideas to realize creative projects. Online at: http://www.organizingcreativity.com/book-as-pdf/

I am curious to know if you ever found a replacement for Mendeley?

Hoi Erik,

I continue to manage my literature — the literature I have read/written and need to cite — with Papers 2. Mostly due to the cite-while-write feature, which I like, and the iOS sync (in contrast to Sente, without having to upload your documents on external servers). But Papers is … well, it’s beautiful, but the company takes a long time to get the software free of bugs — which is the main reason I don’t use Papers 3. But if you are looking for a more social management tool, academia.edu or researchgate might be worth a look.

All the best

Daniel