«Why don’t you teach people to have their own individual voice? … I get that argument, I get the moral and ethical pressure to teach people to have their individual voices. But when I sit with somebody up in my office who’s worried about their career not going anywhere … it can’t be about their individual voice. It’s about what gonna make it valuable to their readers. You need to understand that this program that we have is motivated by those people who have come to us and said ‹our writing is not succeeding› and the whole program is aimed at them. How do you help them succeed.»

Larry McEnerney

How do you write in Academia? A highly interesting presentation by Larry McEnerney of the University of Chicago provides an interesting perspective.

I know (and it’s one of my mantra’s when teaching students) that you have to answer the question «Why should I care?» immediately. And yeah, the role of the field in creativity is a factor to consider. But he expands these points massively — and yeah, going for self-interest is another issue.

BTW, you find a handout similar to the one he used in the video here: https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/u.osu.edu/dist/5/7046/files/2014/10/UnivChic_WritingProg-1grt232.pdf

Given the presentation is quite long, here a few notes about the content:

- Above all, the writing has to be valuable, which is more important than persuasive, organized, and clear. Personally I’d go with the later as hygiene factors — they have to be fulfilled but do not make a paper. The valuable makes — or breaks — it.

- The value lies in the readers, not in the written text.

- Writing is rule governed, but think about the specific readers.

- Problem with learning to write in school/parts of academia: You learned to explain what you know to someone who already understands it (the teacher) because you had to show you have understood it. But explaining something to a naive reader is different.

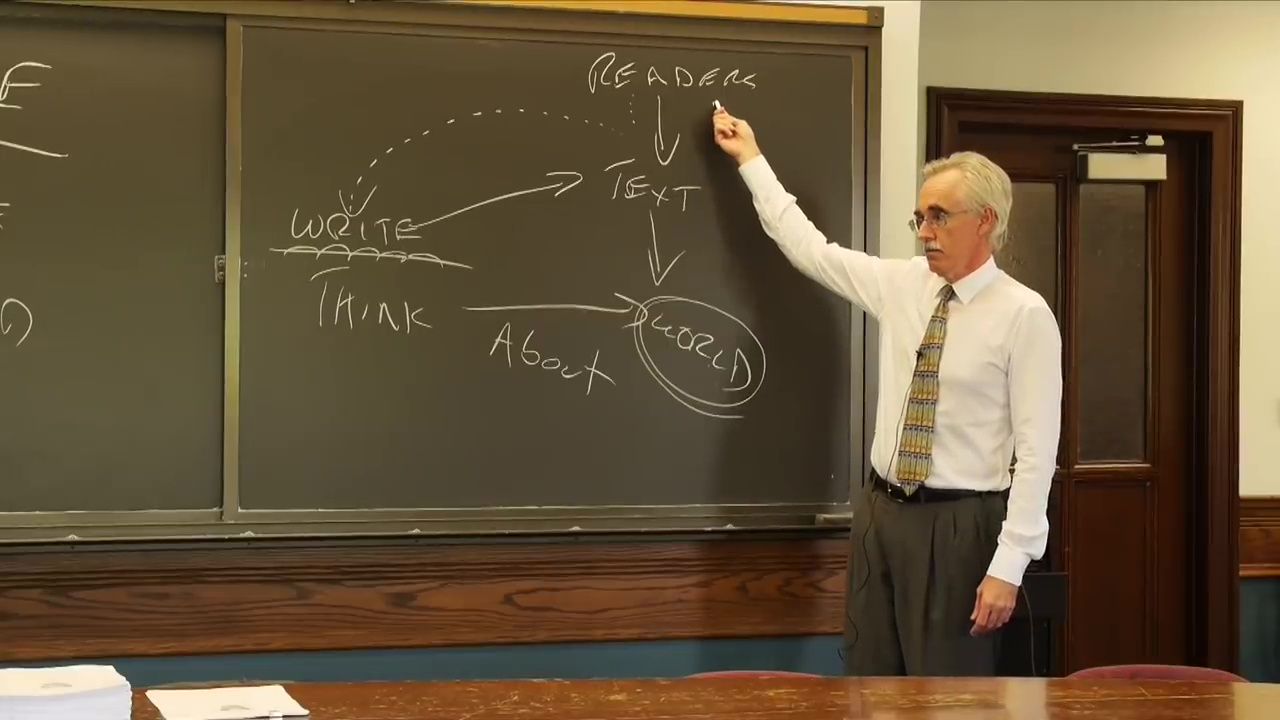

- Writing is not communicating your ideas to your readers, professional writing is changing their ideas.

- Nobody cares what ideas you have. Instead of «Why do you think that?» the reader’s question is «Why should I think that?»

- The readers will challenge what you write — «Nothing will be accepted as knowledge or understanding, until it has been challenged by someone competent to challenge it.»

- Has to show that it is valuable first, do not try to explain it first. Never use important, or new (trivial, lots of things are new, e.g., number of people in this room) or original. The work should be valuable (otherwise do not care).

New knowledge would only be valuable in a positivistic world in which knowledge accumulates. But we do not live in such a world (anymore). Instead, the field (people in the specific scientific community) say what knowledge is. The academic conversation moves through time. Stuff moves in and stuff moves out, the later esp. stuff that was dumb.

- Use the right words to show that you contribute to the scientific conversation, words like «nonetheless», «widely accepted», «however», «although», «inconsistent», «reported», «anomaly». These words create value to the reader (circle the words in the articles you read).

- Every community has its own code, its set of words that communicates value. Some are shared, some are not shared. Create an invaluable word list — should be 10 words in the first two paragraphs.

- You have to know the reader. Half the PhD is learning new stuff, half is learning the readers.

- Words that have to do with the community: «widely accepted» or «reported» — there is a community who wants to understand this. Signal to the community. Problem with flow or transition words («because», «if», «unless», «however», «although», «and», «but») — are not bad, but have nothing to do with value.

- Say that the people in the community are smart. Then show you can advance the community by adding on something or correct this one little thing that is wrong. This approach requires an argument, not an explanation. Have to predict what they doubt (and why should anybody agree that they were wrong). Provide a quick version of why the reader should think that they are wrong in the Introduction to cause them to think that your work might be valuable.

- Don’t go for «I have something new!» — they don’t care.

- Don’t go for «I want to put my voice in the conversation.» — they have no reason to listen to it.

- Instead: «Identify the people with power in your community and give them what they want.» You have to challenge the existing community inside the terms of the community.

- This approach has … ethical issues, can be challenged:

«Why don’t you teach people to have their own individual voice? … I get that argument, I get the moral and ethical pressure to teach people to have their individual voices. But when I sit with somebody up in my office who’s worried about their career not going anywhere … it can’t be about their individual voice. It’s about what gonna make it valuable to their readers. You need to understand that this program that we have is motivated by those people who have come to us and said ‹our writing is not succeeding› and the whole program is aimed at them. How do you help them succeed.» (and he addresses these ethical and moral issues) - Challenge people under the code of the community. There are polite ways to do it and there are insulting ways to do it. If you do it the wrong way you gonna get slapped down, if you don’t do it at all, you get rejected.

«By definition, anything you write has the function of helping your readers to understand better something they want to understand well.» - That’s what it is because that’s what it does. That’s what its job is. The other stuff (structured, clear, etc.) is how you fulfill this function.

- Compare it to a school essay — write an essay to help you think? Okay, but why should the readers appreciate it if you wrote it to think. They are not going to appreciate it just because you wrote it.

- Ideas are not preserved indefinitely, but have to move the conversation in the field forward. It cannot do it if it’s in your desk drawer. And it’s not a bad thing if it’s left behind later.

- Writing is a way to participate in the world, but not by sharing your feelings or your thoughts, but by changing other people’s thoughts. Writing is not about communicating anything about you, that’s not its job. It’s to change the way the readers think.

- Does not mean lying and there are not only the two options of communicating your inner thoughts or lying.

Language has many different functions. - Function of an academic piece is not to communicate your ideas, it’s to change the ideas of an existing community. Sometimes it does it by communicating your ideas, sometimes you don’t, but understand what it’s for.

- Problem (see essay example above) is that we are trained to reveal what we have in our head. But knowledge has no longer something to do with what’s on the inside of people’s heads. Now it’s about what is done in the exterior space between heads (not what they know but what they have done in the field). The relationship between the person and knowledge is like between a farmer and wheat, or a miner and coal — it’s about the value.

- Need instability to make the work appealing: create tension, challenge, contradiction, red flag. Words like anomaly (noun); inconsistent (adjective); but, however, although (transition words). No magic involved, just make it helpful.

- Not hourglass or martini glas model (starts with Generalization, Background, Definition) — is a model of stability and continuity. Shows that the thesis value rests on knowing something that we already agree is valid, but readers look for language of instability, inconsistency, and tension.

- Better opening — open with a problem, e.g., a specific set of readers’ problem or specific reader communities. It must be located in something the reader care’s about (academics: something they want to understand; non-academics: some problem the readers want to fix). Then move tot he solution. Thesis can only be the solution if the readers perceive the problem, so say clearly what the problem is.

- Problem with writing — writer moves horizontally and understands the subject matter better and better, but readers look vertically to search for the value for the problem. They look for inconsistency. The different approaches interfere with reading process, the readers slow down, get confused, get aggravated, and stop after two paragraphs. They look for value, but you are not giving it.

- Problems have two chief characteristics:

- Instability: Situation has to be unstable, show with words like anomaly (noun); inconsistent (adjective); but, however, although (transition words)).

- Language of Cost and Benefits: Use language to show that instability imposes a cost on them, not on you, on them. Or that instability — if solved — offers a benefit for them. Is a different language, the language of cost vs. language of benefit. For example, start with x is great work, but inconsistencies. Okay, but there are tons of it in it, does it cost me anything? Many inconsistencies make no difference, does this one? Or start with benefit: brilliant work, but if change x, huge benefit. Depends on the journal, check for language of benefit vs language of cost. Might not be pattern, but if there is a pattern, use it. Published articles show you the language that works.

- Literature reviews as PhD one of hardest things to do, because you don’t know who the readers are. The function for teachers is to judge the writer (did the student understand it, i.e., did he explain it correctly in the text). The function for professionals is different. They don’t read it to find out if you know stuff about anything. Want to review that enriches the problem. Not just saying x said a, b, c, but to create tension, show problems and inconsistencies, layers of complexity, complication, and tension. Might move forward, but not from stability, but enhance sense of instability. Show the costs to the community, how we can better move forward.

- Do not give background information, but build the problem. There is an enormous difference between the two. Show why it matters — needs the problem. Has to be an error, not a gap.

- Gap not useful because gaps in knowledge are common. Can be small, not important, irrelevant for cost/benefit. Gaps are associated with a bounded view of knowledge, but does not work if knowledge is infinite. If we fill the gap, we still have an infinite number of gaps left. So if you have found and filled a gap, you haven’t done that much.

- Problems are useful. If you identify a problem (e.g., communities uses categories that they do not understand), then address the community. Define them, for whom is it a problem. Use e.g. two sentences to describe the communities who have a problem.

- Problem with interdisciplinary work — who is in your community of readers? Have to address them. Compare a thesis with three people from three different communities. If these are the right three people it is amazing, but with the wrong three people it is a writing nightmare. They define problems and see arguments differently.

- First grade functional writing understands the function of writing, not the rules, or the form, or what it looks like — but what the function is.

As written, a highly interesting presentation. Well worth watching — and yeah, it takes an hour or so. I’m not sure whether I will use the suggestions on this blog. Mostly because this blog is more a space where I share stuff I found useful, or keep things I might use again. And yeah, it has a strong school essay function. I write to find out what I think and why. Some people do it in conversations. I like the written word.

But for scientific papers — yeah, you don’t have to like it, but he has a point. Several, actually.