I filled out an application that said, ‘In Case Of Emergency Notify’.

I wrote ‘Doctor’ … What’s my mother going to do?

Stephen Wright

tl;dr: Emergencies are rare and hard to deal with. People look at the behavior of others to determine how to react. But if all people look at each other for advice on how to act, no one acts. So if you are in an emergency, realize that it is normal that everyone looks around for advice on how to act and thus nobody does anything. Ignore them and do the right thing. Help. If you do, others will follow your example.

Suppose a person you love suddenly collapses. What do you do? If you have participated in a first aid course, you likely have some idea. But what if you encounter someone who collapses on the street? What do you do then?

If there are other people present, likely you will walk past. Just take a look at this video:

Why do so many people walk past? Just imagine the person you love was the one who collapsed in that video. Given the importance of immediate first aid, this person might have died. That can make you righteously angry. And I’ve taken part in first aid courses, where the instructor did get angry. Citing examples where people did die because no one helped, the instructors got angry, claiming: “People don’t care. We live in an individualistic every person for him-/herself society. We don’t consider others as human beings.”

I can understand the emotional outbreak. But what makes me super-angry and depressed is that in almost all cases, this is the wrong explanation. The question why someone does not help but looks on or walks past is one of the human behaviors that is extremely well researched. And it kills me that people assume it has anything to do with character or the like. In fact, in most cases it is not the fault of the bystander that s/he does not help. They fall prey to common psychological effects.

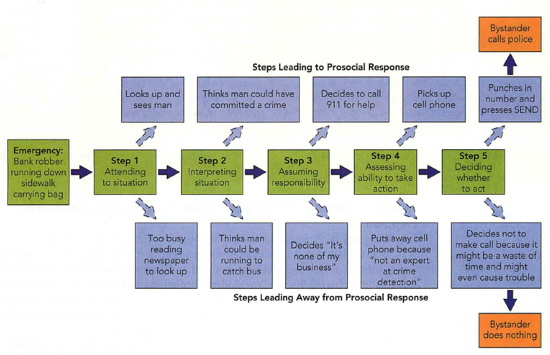

According to Latané und Darley (1970, cited from Baron, Byrne und Branscombe, 2006) there are five steps that determine whether a person helps. Only if the person passes each step successfully does the person help.

Disclaimer: These are “natural” psychological processes. It happens, because human beings are limited. It does not excuse not helping if you notice the emergency. But it explains why many people do not help and it shows ways to make helping more likely.

Step 1: Attending to the Situation: Emergencies are rare, they are unexpected and hard to predict. Given that our attention is limited we do not actively process everything around us. Was there a person lying on the street? Thus, we can overlook emergencies, esp. if we are under time pressure. If someone walks past an emergency, it might be that this person did not notice the emergency.

Step 2: Interpreting the Situation: Emergencies are not always obvious — we only see part of a situation. If you have ever heard children or teenagers playing, they sometimes scream for no reason. Or they might just have broken through the frozen layer of a lake. It can be hard to get it right and the fear of making a fool out of oneself might predispose some people to assume no emergency. The problem is that other bystanders might look at the behavior of other people in the situation and if others do not consider it as an emergency, it reinforces this explanation. It’s a case of “pluralistic ignorance”. Thus, more people usually means a lower likelihood that someone helps. It’s counter-intuitive, but true. Thus, if other people do not react to something that might be an emergency, it does not mean that it really is no emergency. They might just have done what you did — look at others for guidance and thus do nothing. If in doubt ask. You feel better and it just might save a life.

Step 3: Assuming Responsibility: Even if people notice the emergency, someone has to feel responsible to do something about it. In some situations, the issue of responsibility is clear, e.g., if the police or the fire department is present. But in an everyday situation, someone has to feel responsible. Again, it’s more likely that someone helps if — beside the victim — there is only one person present. There is no one else there who could help. But if many people are present, the issue becomes “problematic”. People might look at each other, each waiting for the other “probably better qualified” person to help. Thus, no one does anything. This diffusion of responsibility usually means that no-one helps. Thus, if there is an emergency, realize that it is “normal” (but deadly) that no one makes the first step. They are all looking at each other waiting for someone to do the first step. On the bright side, others usually join in the second someone does take the first step. So ignore the rest and do your best. They will join you if you do.

Step 4: Assessing the Ability to Take Action: Even if you feel responsible to help, it is not enough. You need to come to the conclusion that you have the ability to help. Helping a drowning person might be hard if you cannot swim. But I don’t think that a lack of ability is any excuse today. First aid courses are offered by many institutions and you can and should do them every few years or so, just to feel comfortable to have the ability to help. But even if you do not know what to do, doing something is usually better than doing nothing. There are two things you should keep in mind: First, self-protection always comes first. Nobody wins if there are two people dying instead one just one. Second, you likely have the ultimate tool for first aid in your pocket: Your cellphone. Even if you do not dare to enter the water, or stop at the highway, you can call the police or fire department and inform them. We live in a technological society, why not use it to save lives. Thus, if you are unsure whether you have the ability to help, doing something is usually better than doing nothing. If anything, do call for help.

Step 5: Deciding Whether to Act: Helping others is risky. There are costs and risks associated with helping others. If you stop by a highway, you might become a victim of crime. If you try to save someone from drowning, you might drown yourself. However, with cellphones there usually is no reason not to at least call for help (see previous step). Thus, do something where the potential gains are greater than the costs. If you can, help directly. If not, call for help yourself.

Other factors and Conclusion

Of course, there are a lot of moderating and mediating factors that make helping more or less likely. But without going into the details, just remember that it becomes less likely that people help the more people are present in the situation. If you notice something on a crowded street, that’s the moment when you have to take a critical look and assess the situation for yourself. Most likely, no one else will. Unfortunately, it is “normal” (but not excusable) that no-one helps, because people miss the situation, do not see it as emergency, do not feel responsible, feel like they lack the ability, or the perceived costs outweigh the benefits of helping. It’s not fair, but if something happens, you need to help first to make others help as well.

And if you need help yourself and many people are present, pick someone who looks confident and specifically ask that person for help.

Literature

Baron, R. A., Byrne, D. & Branscombe, N. R. (2006). Social Psychology (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

Note: I’ve written a similar posting on a German blog.

Note 2: Yup, it’s off-topic. But it’s also something I wish everyone would know, because I believe it might convince more people to help in an emergency. And as someone who likes to see at least a few people alive, I care about that.