“Why don’t you ever look beneath the surface, young man! I laugh because I dare not cry. This is a crazy world and the only way to enjoy it is to treat it as a joke. That doesn’t mean I don’t read and can’t think. I read everything from Giblett to Hoyle, from Sartre to Pauling. I read in the tub, I read on the john, I read in bed, I read when I eat alone, and I would read in my sleep if I could keep my eyes open. Deety, this is proof that Zebbie has never been in my bed: the books downstairs are display; the stuff I read is stacked in my bedroom.”

“The Number of the Beast” by Robert A. Heinlein

I am putting reading and using literature in one posting for two reasons: First, I have already written a lot about reading literature — on this blog and in my book (which I strongly recommend that you download) — so I can refer to these postings for the reading part. And second, because reading and using is very intimately tied together. How you read your literature determines how you can use it.

You can read paper after paper without making notes — and you will likely read a lot, but it is unlikely that much comes out of it (except the frustration of reading the same paper multiple times). Or you can read smart and use the — correctly cited work of others — for your own works. After all, it doesn’t matter what is written in the paper that much what is really important is what conclusions you draw from it, how it helps your work, your argument. Facts and Thoughts in articles are the LEGO(R) building blocks for you thesis (which you have to cite correctly) (Wessel, 2011).

The goal here is to have the literature that refers to the topic you are researching available for your work and in a way you can use it. You must quickly deal with huge amounts of information and make it useful for your work. Mostly, this means two related but very different things:

- Create a model/multiple models of the area of interest

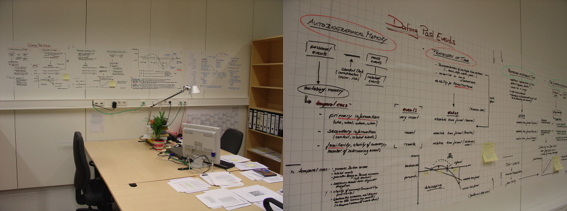

This is the high-level view on your research subject that prevents you from getting lost in the details. Whiteboards and MagicCharts are very helpful here. Alternatively, you can use Keynote or PowerPoint if you want to keep it for your eyes only. Here you organize and tie the pieces together. - Have the information easily available on the right level

This is a collection of the information on the level that you cite it in your papers and presentations. Outliners are really helpful here.

In any case ensure that you always know where the information you use comes from — what was your idea and what was not your idea! I cannot stress this enough. After working for years with texts dealing with the same subject and writing about it yourself, you might confuse what you have written yourself and what others have written. Especially if you take up the specific language style of the community you are working in. And once you have use someone else’s text without proper acknowledgement it does not matter whether it was deliberate or not — you committed plagiarism, a cardinal sin in science.

There is really only one solution to this — first get everything you cite as a local copy. Have it on your computer. If it’s a website, print it as PDF, if it’s a paper book, scan it. Then save the file with the standard file format (authorname_[authorname_]year.pdf, e.g., smith_1960.pdf). Have a folder or datebase where you put all your literature files and work only with properly names files. Putting all literature in one collection allows you to quickly see when two different works have the same name (happens, e.g., there are a lot of smiths who did work in 1960). If this happens simply add an _b, _c, etc. to the name. But do it before you mark your notes with this source information! You need to be able to track all notes to their proper source — so carry the correct filename along in your notes!

Seriously, even a PhD thesis takes years and if you do not it correctly in the beginning, you have hell to pay later. And if you decide to work in science you need this kind of accountability. A psychologist specializing in writing once said that you can see the intelligence of the person in the way this person takes notes. I think this is a correct assessment when it comes to dealing with scientific literature.

The Model View

It’s easy to lose track of the “grand picture” when you are working on the details. Put your work into context and create a model/models of the topic you are interested in. Like written, whiteboards and MagicCharts are very helpful here — you can keep your model in view every day and augment it.

On the other hand, some labs are pretty … backstabbing, so if you are concerned that colleagues or guests might steal your ideas (and with a camera in almost any cellphone/smartphone very easily steal your ideas), keep the model on your computer by using Keynote or PowerPoint.

The Detail View

In science, you have to attribute the ideas you use — the building blocks on which your thesis and your research in build — to their proper source. This means keeping detailed notes. You do not only need to read the literature, you must make sure that you can use each idea for your own work. This means that every unit of information, which can range from an idea for a single dependent variable up to the result of a meta analysis, should be treated as a LEGO(R) building block for your work. Not to overly stretch the metaphor, each LEGO(R) brick differs in “weight carrying capacity”. The personal communication with a fellow researcher has not the same weight (durability or “weight carrying capacity”) as an experiment or a meta-analysis. Going from least to most durable, the order is probably: personal communication — opinion piece — experience report — case study — survey — quasi-experiment — experiment — literature review — meta analysis. Imagine each stone you find (= each unit of information) as having different stress tolerance or different durability (imagine each stone a different color, each color depending on the source of the information, from personal communication to meta analysis). Some (e.g., experience report) might crumble under minimal scrutiny, others are pretty indestructible (e.g., meta-analysis). Your line of argument when you use other people’s research to build your own work will break at its weakest point. So be sure to use enough high quality stones in your work.

But how can you ensure that you have this information available? There are multiple ways. At the very least you should make notes about each source you read. The easiest way is probably using a text or Word file with a template (e.g., “source”, “main points”, “how to use the information in your work”). A very successful psychologist did use a database for the studies he read (he was not interested in non-experimental papers). His default fields included the standard information you need to cite the article and the main information about the study itself: independent variables, dependent variables, central results, authors interpretation, his interpretation, etc. At the very, very least make notes, even if it’s only on the printed paper itself.

Having the information available

Personally, I am like a plough when it comes to reading literature. First of all, it makes no sense unless you want to cultivate the land. If you do not know for which study/paper you want to use the paper you read it will not work. Because here’s the thing — you highlight everything you need (for you own paper) from the source you are reading when you are reading it … and if you do not know for which purpose you are using the paper you read you might as well (and will) highlight everything. And then you stand, with all your lore, no wiser than before (to misquote Goethe). But once you know for what you want to use the paper you are reading it is very easy to quickly read and use dozens of papers per day.

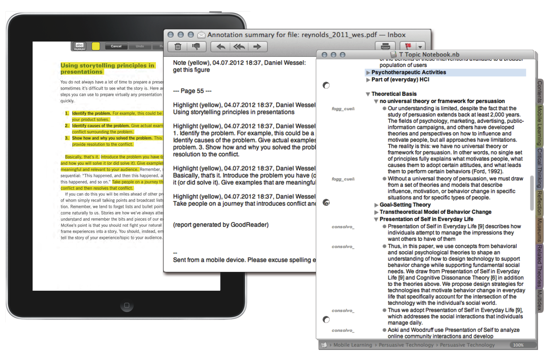

And regarding the highlighting and getting the notes — isn’t this kinda too much work? Not really. One of the best investments I ever did when it came to my work was buying a tablet (an iPad, actually). I read literature digitally, highlight the information I want to use in GoodReader — and then simply export the highlighted text per eMail (you might need to clean it up a little). It does not get more comfortable than that (I strongly recommend the “Reading digitally” entry in the book “Organizing Creativity” here). If you are wondering how to get the books as PDF in the first place, there is also the “Digitizing Information” entry in the book or these two postings: Creating a Virtual Library and 109 scanned books later ….

However, getting the relevant information is only the first step — how do you keep your notes and how do you keep it connected to the original source?

Using an outliner with cell tagging

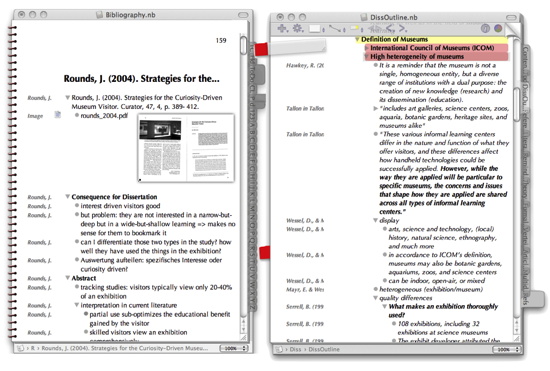

Personally, I highly recommend Circus Ponies Notebook. It’s a great outliner (if you do not know what an outliner is, see the book or this entry — and no, it has nothing to do with an outline view of Word or the like, it’s totally different). Unfortunately, Circus Ponies Notebook is a Mac program, so Windows users are lucked out. But perhaps there is a similar software that combines the two features that make Circus Ponies Notebook invaluable for dealing with literature (if you adhere to the LEGO(R) bricks metaphor):

- You can keep each unit of information in a cell of its own (and given that it is an outliner, you can hierarchically order the cells in your fashion)

- You can tag each cell with the source information (which sticks to that cell if you copy & paste it in the right way)

This means that you can read the literature, highlight the (for you) useful parts, export them, copy & past them as an outline into Circus Ponies Notebook, tag the cells with the source information (in Circus Ponies Notebook this is called a “keyword”), and then use the cells as LEGO(R) bricks for your own work while always maintaining the source information of the information units you use. It seems like a lot of work, but it pays off later. And you can create pretty usable notes this way:

One of the next postings will deal with a possible workflow, but here it is sufficient to say that you can use Circus Ponies Notebook (or any outliner which allows tagging of cells) this way. For more information see Circus Ponies Notebook: The Best Tool for Structuring Creative Writing Projects (esp. Research Projects) and Circus Ponies Notebook for Academic Writing (e.g., Thesis Writing). If you keep your research this way, you can create a large content outline (see How to create a content outline in Circus Ponies Notebook) which can allow you to quickly write your thesis (or paper, or whatever, see How to Write a Dissertation Thesis in a Month: Outlines, Outlines, Outlines).

Personally I favor topic notebooks where you have all your information regarding a subject available (in citable form, meaning that you can copy the outline cells from your topic notebooks to an article notebook and thereby creating a new outline that keeps the source information intact). This will also be the subject of another posting (actually, I have already covered it in the book — page 350; Acrobat page 176).

But that’s it for now, more in one of the next postings.